Hidden History

by Rev. David Pettee

Here in the North, we have inherited a powerful historical amnesia when it comes to the memory of slavery. Where I live in Massachusetts, we still worship the stories of the Sons of Liberty. We still teach “The Midnight Ride of Paul Revere” to our school kids. Every third Monday in April is Patriot’s Day, when we commemorate again that first shot fired on Lexington Green that was heard ‘round the world. In Massachusetts our license plates remind us that we are the ‘Spirit of America.’ We are the good guys.

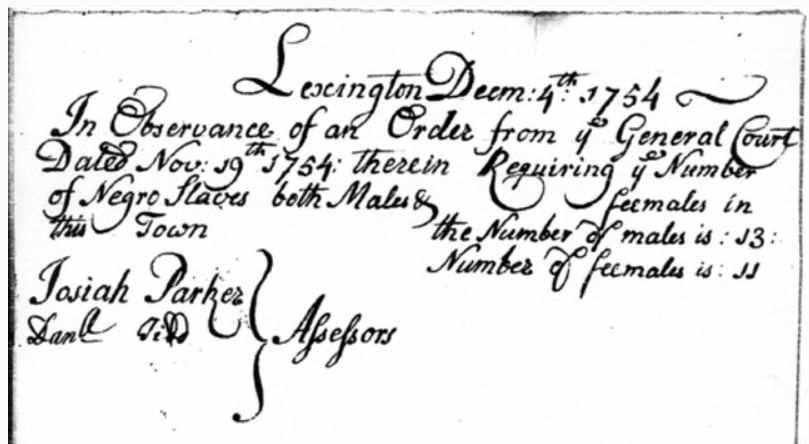

In 1754, the Crown requested that every city and town in Massachusetts report the number of slaves over the age of sixteen. 114 communities responded to the census. 109 recorded at least one slave. The town fathers of Boston dutifully recorded 989 slaves, representing nearly 9% of the population.

989 slaves? In Boston? How come I had to discover this fact by accident?

Within walking distance of where I work in downtown Boston, there are numerous buildings and sites that pay homage to Boston’s storied colonial past. Every day on my way to work, I pass the Robert Gould Shaw 54th Regiment Memorial on Beacon St. Directly across the street from the memorial is the Massachusetts State House, built on property once owned by John Hancock. We all know John Hancock. Or do we? The plaque that mentions where his house once stood conveniently neglects to mention that Hancock was also a slaveholder.

Today, Bay Staters are very proud of our abolitionist past. We forget that in 1835, William Lloyd Garrison, editor of The Liberator, was nearly murdered by an angry mob on the streets of Boston. In the 1960’s, in the name of urban renewal, the office where the newspaper was published fell unceremoniously to the wrecking ball.

At the base of Beacon Hill in the Boston Public Gardens stands a statue of Charles Sumner, widely considered the most radical abolitionist in the United State Senate before the Civil War. In 1856, after Sumner was nearly caned to death in the Senate chambers by South Carolina Representative Preston Brooks, hundreds of people sent money to Brooks so he could buy a new cane. It is quite understandable that many Massachusetts citizens were outraged! Few, however, questioned Sumner’s outlandish claim made two years before, when he thundered on the Senate floor that, “No person was ever born a slave on the soil of Massachusetts.”

I can still vividly remember the first time I recovered the forgotten story of slavery in my own family. In 2006, I innocently upgraded my Ancestry.com subscription and was stunned to find the 1774 Rhode Island census that indicated that my ancestor Edward Simmons owned four slaves in Newport, RI. I drove to Newport the following day to get to the bottom what was obviously some mistake.

It wasn’t. Instead, I found eleven more Newport ancestors who enslaved Africans.

Fast forward to 2012. I have since discovered thirty additional slaveholding ancestors and one ancestor who was a captain of at least five voyages in the transatlantic slave trade. All these people lived only in New England.

So much for slavery as a Southern institution…

I first heard about the work of Joe McGill last year when I was in South Carolina co-representing Coming to the Table at the annual meeting of the National Genealogical Society. I was struck by Joe’s vision of wanting to preserve the few existing slave quarters that are still standing in this country. Lifting up the history of any building forces us to reckon with the meaning of this structure. It is so easy to forget that slavery helped build the North because it is so hard to see that legacy any more.

When the invitation came to spend a night in the slave quarters at the Bush-Holley House in Greenwich, CT with Joe, Grant Hayter-Menzies and Dionne Ford Kurtti, I jumped at the prospect. I wanted to try to better understand what enslaved people must have experienced every night. I wanted to honor those who were forced to live here.

Even with a Thermarest pad under my sleeping bag, the floor felt so hard and unforgiving. While the attic offered some privacy, it was easy to hear noises from the floor below, and the creaking as people walked up and down the stairs. The people who lived in that attic through bitterly cold winters and oppressively hot summers must have spoken in a whisper, hoping to maintain as much dignity as they could—dignity that was constantly undermined by people just like my ancestors.

As I lay awake, I thought about Joe and Dionne, asleep on either side of me, and wondered what this experience must be like for them, sharing this space with two descendants of slaveholders. The rain that pitter-pattered on the roof was a timeless noise that helped me finally fall asleep. Startled by snoring, I awoke quite suddenly at 4am, all twisted in my sleeping bag, feeling hot, clammy and disoriented. Back in 1750, the people who lived in that attic were probably already in the kitchen baking bread by 4am, preparing breakfast for their masters.

Despite the enjoyable company, it was most certainly not a restful night.

To learn more about slavery in the North, click here.