Connecting and Healing Through Action

by Phoebe Kilby

When I began my quest to determine if my family had owned slaves I focused on slavery alone and not the repercussions of it. I quickly learned after meeting descendants of people my family enslaved, that wounds inflicted during the Civil Rights era, a time in which they had been denied educational opportunities and terrorized for demanding change, were much more impactful to them than scars left from slavery.

When I began my quest to determine if my family had owned slaves I focused on slavery alone and not the repercussions of it. I quickly learned after meeting descendants of people my family enslaved, that wounds inflicted during the Civil Rights era, a time in which they had been denied educational opportunities and terrorized for demanding change, were much more impactful to them than scars left from slavery.

I realized that if I were going to do something to nurture healing, I would need to address these more modern wounds.

Unequal access to education is a legacy of slavery. Most slave owners kept their slaves from being educated because they thought education could lead to rebellion. After the Civil War, the systematic reluctance to provide a proper education to African Americans continued. Many U.S. communities offered schooling to African Americans but in separate poorer quality facilities with limited resources.

The descendants of the people my family enslaved experienced these education disparities firsthand.

Betty and James Kilby attended segregated African American schools in Warren County, Virginia. There was no school available for them beyond 8th grade in their town. Their father, James W. Kilby, sought the help of the NAACP in filing suit to open the local school to his children. This was 1958, four years after the landmark U.S. Supreme Court ruling in Brown vs. Board of Education.

When the courts ruled in the Kilbys’ favor, the governor of Virginia closed Warren County High School to prevent its integration. The court ruling and school closing caused backlash against the Kilbys. They received nightly death threats via phone, their house was shot at and their farm animals poisoned. I cannot imagine the fear this created.

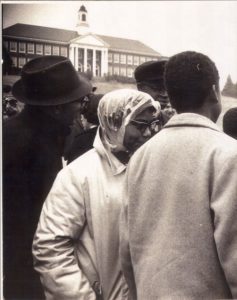

Eventually, the Federal court ordered the school reopened. Betty, James and 21 other African American children entered the school for the first time on February 18, 1959.

When I learned this history, I was proud of my Kilby cousins and ashamed of what Warren County and Virginia leaders had done to them. I searched for ways that I could help them heal from these wounds and consequently got involved with a group James formed called the Historical Education Movement (HEM). This group honors his father’s work in integrating the local high school and continues his work in the community.

I worked by James’ side to petition the current school board to name the former high school after his father. We were not successful in that effort, but we were able to convince the school system to allow us to host a commemoration of the 50th anniversary of the desegregation of the school in February 2009. The town of Front Royal subsequently renamed the road in front of the high school Kilby Drive.

James Kilby at the dedication ceremony for Kilby Drive

After James expressed an interest in hosting a “community conversation on race,” I applied for a Coming to the Table mini-project stipend to organize such a dialogue. It included: African Americans who integrated Warren County High School; African Americans who chose to attend the all-black high school that was quickly built to avoid integration; whites who were shut out when the high school was closed; whites who attended an all-white private school; a teacher; a bus driver; and two current assistant superintendents of schools. At the end of the dialogue, the group came up with an action plan to help heal the community.

One of the actions was to support placing a historic marker at the school. James and one of the assistant superintendents of schools and I worked on an application to the Virginia Department of Historic Resources. The marker was approved, and the dedication ceremony for this marker took place on June 8, 2011.

Students of the integrating class in front of the marker

Through these actions, I believe some healing has begun. James and I have shared our family histories. We have worked together to honor his father and their family’s bravery during school desegregation. We have reached across the racial divide, inviting others to join in dialogue. And we have become friends. I see progress towards racial healing and reconciliation in our families and in the community.